|

Fillmore Historical Museum Marks 95th Anniversary of St. Francis Dam Disaster

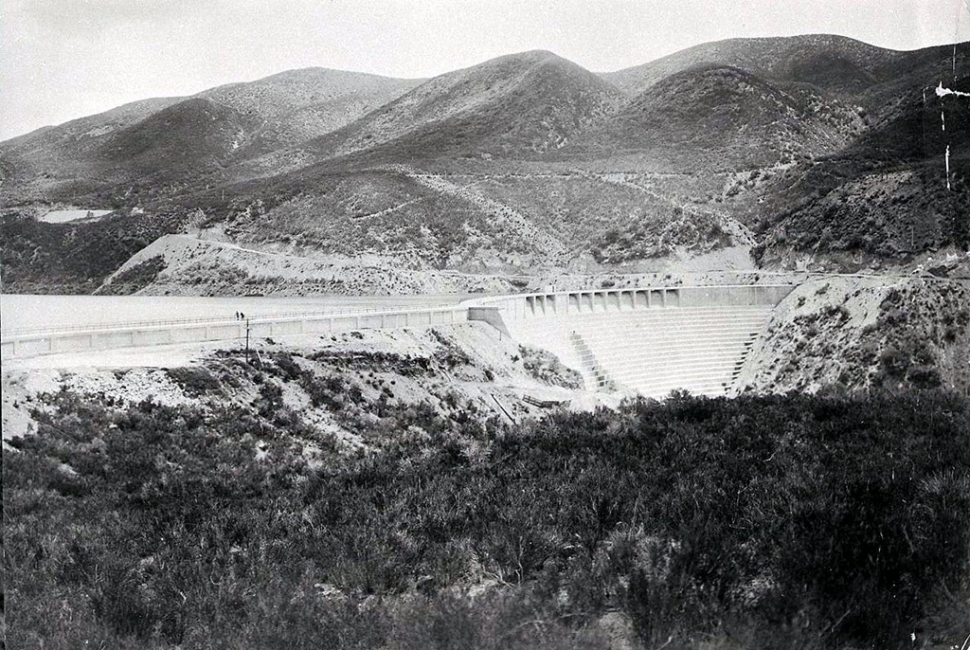

Above is the St Francis Dam a few days before the collapse took place on March 12, 1928. March 12 and 13, 2023 will mark the 95th anniversary of the St. Francis Dam Disaster. On March 11th at 1 pm there will be a presentation about the dam collapse at the Fillmore Historical Museum Depot. Admission is $5 for non-Members. Museum Members and children under 12 are free. John Nichols who wrote a book about the dam will also be there to talk about how he came to write the book. For tickets, go to www.fillmorehistoricalmuseum.org/event-details/st-francis-dam-disaster-a-look-back-95-years. Photos courtesy Fillmore Historical Museum. By Gazette Staff Writers — Thursday, March 9th, 2023

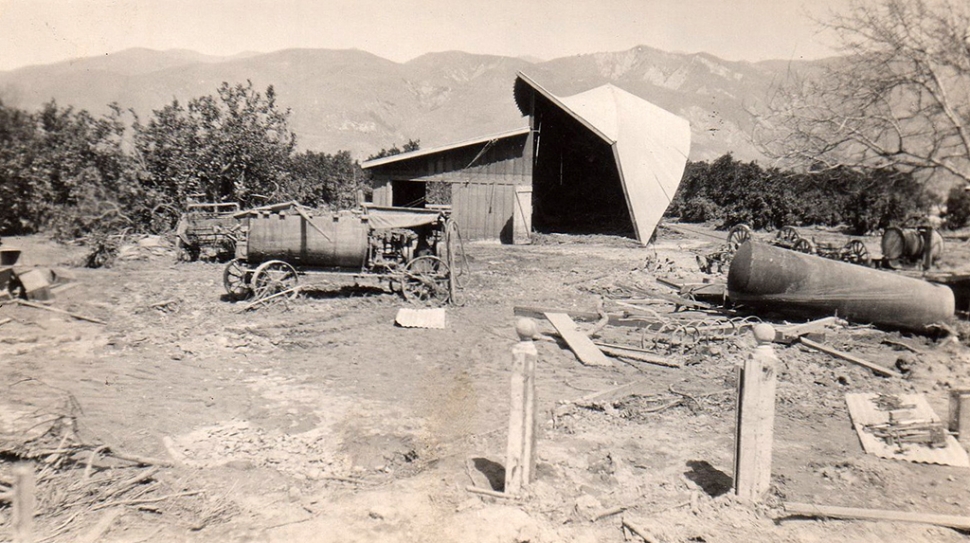

Above is the Chaney Ranch on Guiberson Road, after the flood hit. Courtesy Fillmore Historical Museum We are sharing an article originally published in Empire magazine, March 4, 1951 and then reprinted in Reader’s Digest, April 1951 which was written by William F. French, father of Dr. William French who practiced in Fillmore for many years. Our thanks to Susan M. J. French for sending it to us. The Dam with the Feet of Clay, By William F. French Monday, March 12, 1928, dawned clear and sunny over California’s lush Santa Clara Valley with its orchard of citrus, walnuts and apricots – and over the lake that sparkled behind St. Francis dam, a mighty concrete barrier thrown across a wild canyon high above the valley. No hint of impending disaster disturbed the surface of the giant reservoir which store 1,600,000,000 cubic feet of water for thirsty Los Angeles, 45 miles o the south. But Dan Mathews, an employee at Powerhouse No. 2, a mile and a half below the dam wasn’t looking at the scenery that morning. He saw only trickles of muddy water running down the west wing of the dam and oozing around its end. Completed two years before at a cost of $2,500,000, the dam had been the subject of heated controversy from its inception. Below it, Santa Clara Valley growers had sought injunction after injunction to prevent its construction; they feared it could never be anchored firmly enough in the adobe and shale walls of the canyon. Above it, embattled ranchers had dynamited the aqueduct that carried the water past their lands, and had killed Los Angeles water-system guards. Despite the litigation and open warfare, Los Angeles had backed the judgment of William Mulholland, chief engineer of the city’s water system, and the dam was finished in May, 1926. To Dan Mathews the water seeping out from the dam’s west wing that day in March 1928 spelled trouble. He couldn’t risk spreading panic with what might be a false alarm, but he did report his discovery to his superior. Then he warned his brother to get his family out of the cabin by the powerhouse. That night in Bardsdale, 28 miles below the dam, the George Boardmans put out their lights with the usual feeling of security. Across the little Santa Clara River, in Fillmore families were returning from the movies. Upstream, near the town of Piru, men in the power company’s construction gang had let their campfires burn low and fastened their tent flaps. Unknown to anyone, the trickles of water seeping around the dam had turned now into streams that gnawed at its feet of clay. About midnight the dam let go at both ends. Twelve billion gallons of water went thundering toward the sea – a 125-foot-high deluge of death and destruction. Powerhouse No. 2 was engulfed in one roaring splash. The houses of its workers were buried under tons of mud and broken concrete. Not a soul escaped. With demoniac fury the gigantic wave cut a channel toward the Santa Clara River. Soon the roaring wall of water, now carrying automobiles, railroad cars, houses and tractors, spewed into beautiful Santa Clara Valley. There it spread out, rolling and tossing huge boulders like pebbles snatching up trees and houses, tearing bridges from their foundations, ripping up railroad tracks, snapping poles and power lines. There is a fall of 1200 feet from the dam site to Piru, a hundred million horsepower of merciless destruction roared down upon the 20,000 residents of the Santa Clara Valley’s mile-wide strip of orchard and garden. Traveling at express-train speed, the great wave struck the power company’s construction camp. Not a man there had time to get his tent-flap open before the whole camp, heavy equipment and all, was carried away. So unexpected and deadly swift was the charge of the water that an estimated 50 cars were swept off Highway 126 paralleling the Santa Clara River. Some drivers lived to report outrunning the flood, but those caught where the road was close to water level never had a chance. Weeks later, automobiles were dug out of the debris and mud 20 miles from where they were engulfed. Others, believed to have been washed into the ocean, were never found. After having destroyed the construction camp and all but five of the 80 men in it, the deluge reached the Boardman home in Bardsdale, ten miles downstream. George Boardman recalls: “That night my 14-year-old son Donald and I were sleeping in the tenant house. I woke up to find the place rocking like a ship in a hurricane. Suddenly the little house was tossed in the air. It landed on its side, lodged in the top of a giant walnut tree. We fought free of the building, for the big tree was already being uprooted. As we worked our way shoreward from treetop to treetop, the terrible force of the torrent threatened to wrench our arms from their sockets. “The first big wave smashed everything in its path and swept the debris along like a battering ram. It was a mile long an it passed through like a runaway train, but we were in the 30-feet-deep water that followed it for half an hour. “Above the roar of the water leveling our beautiful citrus groves we could hear the crash and smashing of houses and breaking trees and poles. Parts of houses, splintered timbers and tree trunks striped of limbs would shoot out of the water and crash on the racing maelstrom of debris. That was the most horrible thing about the flood – the deadly debris. We saw a two by four pierce the side of one of our horses, and heard his almost human screams. Cries and shouts for help came from all sides. Somehow Donald and I reached dry land, a mile downstream.” More than 600 homes were destroyed that night. An estimated 700 lives were swallowed up by the avalanche of water which wiped out the low-lying parts of Castaic, Camulos, Bardsdale, Piru, Fillmore, Santa Paula and Saticoy. The flood passed quickly (rescue workers were crossing the riverbed on foot by nine in the morning) but it left a 50-mile long swath of uprooted orchards and debris covered land. Citrus grower Frank LeBard, whose rescue efforts started while the waters were at their height, shudders in recalling what happened. “It was ten times worse than a flood. The water wasn’t merely driving people from their homes – it was killing. I saw sudden whirlpools drag struggling humans and animals out of sight. Cries for help were cut short by blows from the whirling debris. “Hitched to a tree by a rope, I waded out as far as I could stand the pull of the current. I grabbed a man. When I laid him out I saw a heavy bolt sticking through his head.” The flood performed weird tricks. A month after the calamity, a man from Bardsdale saw what looked like his horse working in a field near Saticoy, 20 miles away. The farmer using the animal said he had dug it out of the mire at the foot of his property. Response to the area’s needs was swift. The day after the disaster a half-dozen field hospitals werein operation and Red Cross tents lined the 50 miles from the dam to the sea. Hundreds of professional and volunteerworkers searched for the living and the dead in 20-foot-deep silt and debris. President Coolidge telegraphed an offer of federal help. But Los Angeles seemed to be meeting all needs. It was sending caravans of trucks, scrapers, power shovels and derricks, and soon had more than a thousand workers in the stricken valley. More than compassion inspired its efforts. The city had constructed the dam in the face of bitterprotestsfrom the people in the area. Recognizing its liability, it was attempting to meet its moral obligations. The city began paying damage claims less than a week after the dam broke. “Los Angeles didn’t quibble in settling,” recalls George Boardman. “Here in Ventura County we were allowed $500 an acre for damage to land without trees, and up to $3000 an acre for prime groves that weredestroyed. Death benefits of $7000 to $10,000 a person were paid.” While it is not known how much Los Angeles paid in all, residents of the valley say $30,000,000 is close. On March 17 Governor Young ordered a state investigation of the tragedy, and William Mulholland, father of the original project, inspected the ruins of the dam and the desolated valley. The grief-stricken engineer accepted full responsibility. His final statement to the investigating jury was, “I envy those who died.” Mulholland immediately retired from active duty and, within a short time, died. The St. Francis dam had claimed its final victim. |